Turtle Shell Chess

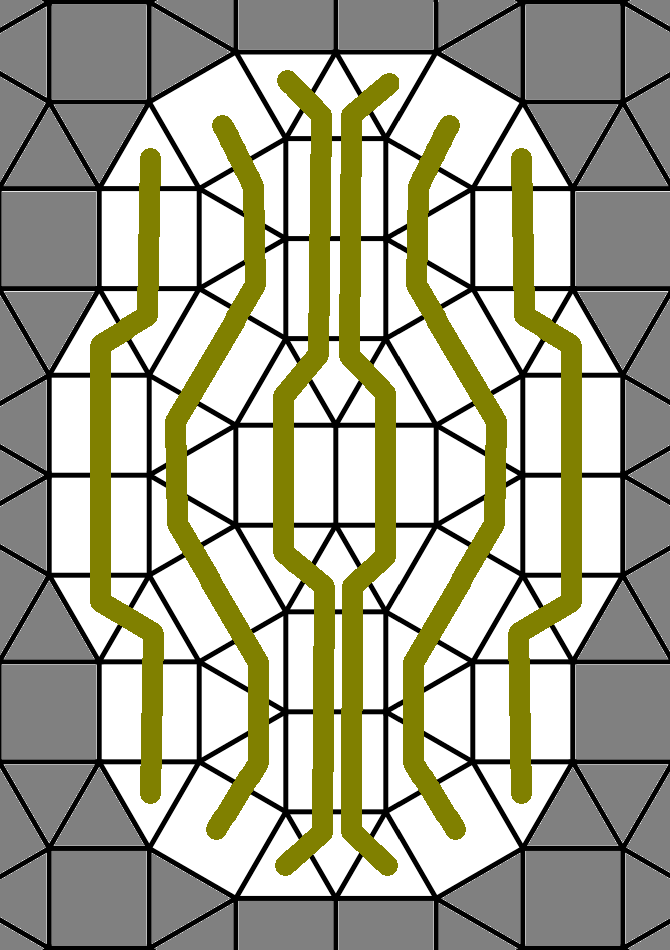

Since 1994, I have wanted to create a playable chess variant using a particular tessellation that the Wikpedia calls a 33344-33434 tiling.

When I was trying to come up with a chess variant with this tiling back then, my then roommate said my board looked like a “Turtle Shell”, which is why this variant is called “Turtle Shell Chess”.

It took me 28 years, but I have finally formalized the rules for “Turtle Shell Chess”.

This is an open content public domain chess variant: Anyone is free to implement this variant or make their own modifications to this variant without asking permission. This variant, its rules, the wording used here to describe it, and all diagrams here (including the free to download high resolution board diagrams) are all public domain.

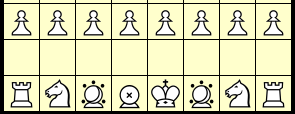

Setup

This Chess variant is played on a board using a tiling which combines squares and triangles. Pieces are placed and moved inside of the squares and triangles. The places where pieces may go are called cells; there are 64 cells in Turtle Shell Chess.

Pieces

To illustrate the pieces, it is first necessary to illustrate the notation then the rows and columns.

The board has 10 rows in it. Because of the nature of the tiling, some cells are in more than one row. Rooks can move left and right along rows.

The board has six files. As with rows, some cells are in more than one file. Rooks can move up and down files, and pawns can move as well as capture one square towards the opponent’s endzone on a given file.

A rook may move any number of cells along a row or file. A rook must make an entire single move along the same row or file; for example, a rook on D0 may move to D3 (which is on the same file) but may not move to E3, because moving to E3 is only possible from D0 if the rook changes the file they are on during the move.

A guard (Queen in the illustration because the Fers it is based on was a very weak piece) may move or capture to any cell it shares an edge with. If a cell is a triangle, a guard may move or capture to any of the up to three adjacent cells. If the cell is a square, a guard may move or capture to any of the up to four adjacent cells.

A knight in Turtle Shell Chess may move or capture to any cell that it shares a corner with, as long as the cell in question does not share an edge with the cell the knight is in. A knight, if in a triangle cell, may move to up to six different cells. If in a square cell, a knight might be able to move to up to eight different cells.

A king in Turtle Shell Chess moves like a guard, but is royal (it can not be captured, it can not move in to check, it can be checkmated). If a king ends its turn on a square in the opponent’s end zone without being in check, the game is immediately won for the person who moved their king across the board.

A pawn is like a Shogi pawn: It moves and captures one cell forward along a given row. It may move one square forward towards the opponent’s endzone along a file. If a pawn ends its move in the opponent’s promotion zone, it may, at the player’s discretion, promote in to a rook immediately after ending its move in the promotion zone. If a pawn ends its move in the opponent’s end zone, it must promote in to a rook immediately after ending its move. For example, if the white player moves a pawn from C5 to C6, they may make the pawn on C6 a rook on the same turn the pawn moved from C5 to C6. A pawn must have moved on the same turn when it is promoted. A white pawn on the E2 triangle cell may move or capture to either the D3 cell or the E3 cell. A black pawn on the E7 triangle cell may move or capture to either the D6 cell or E6 cell. Otherwise, each pawn may only move to the cell immediately in front of it on the same file.

To help illustrate the pawn and king, it is necessary to show the promtion zone then the end zone. First, the promotion zone

And the end zone:

Rules

The object of the game is to checkmate the opponent’s king, or to place one’s own king on a square in the opponent’s end zone without the king being in check. Stalemate is losing for the player giving stalemate.

Similar to Xiangqi, there is a complicated “no chasing” rule to avoid repetition: If making a move which recreates a position previously played in this game, with the same player having the move as the previous position, the attacking player must stop the loop. An attacking player is defined as the player who, for all board positions in the loop, just after the attacker has moved, more capture threats (including check) are on the board regardless of the color of the piece making the capture threat. This is calculated by adding together all possible capture moves for each unique board position in the loop per player. In case this sum is the same for both players, the player who gives check more often (i.e. has more king capture threats, where a double check is 2 threats) in the loop of moves is the player who must make a different move to break the loop. In case the sum of possible captures is the same for both players during the loop, and both players give the same total number of checks (0 or more) in the loop, the player whose move starts the loop must make a different move to break the loop. This is a modified “Ko” rule. When playing with a computer, the computer would enforce this rule. When playing on a physical board, the rule would be more subjectively enforced: Someone appearing to attack an opponents piece resulting in a repeat of a previous position would be asked to stop the attack by making another move or forfeit the game.

Notes

This game may be played with an ordinary chess + checkers set using a custom printed board; place a checker under a pawn to indicate the pawn in question has been promoted. Here is a free high resolution board image for playing this game, both as a PNG image and as a PDF file:

There is a free Zillions of Games implementation of this game available, but one will need a license for Zillions of Games as well as a computer which can run Zillions (I have tested it in both Windows 10 and Linux using Wine; it runs in both environments):Notes about the game design:

- In terms of strategy, this game feels more like a combination of Shatranj and Xiangqi than like standard chess

- The game in some ways resembles Chinese Chess (Xiangqi) more than chess. The king is weaker, the pieces are more like Xiangqi pieces than chess pieces (read: No bishop) and the pawns can only move straight ahead like in Xiangqi and Shogi.

- The game has been designed to minimize draws: Pawns can quickly promote to rooks, the king has a limited move making it easier to mate, and in case of not having enough mating material, the game can be won by simply racing the king to the other end of the board.

- The game seems to be strategically more simple than western Chess, since pawn chains don’t exist, but it obviously hasn’t been played enough for anyone to know how deep the game is.

- While a number of hexagonal chess variants have been invented, chess variants using other tilings are relatively rare; see below to links to some of those other variants.

- The knight is more like the ferz piece, but it is called the “Knight” here because that is a more familiar name, because “fers” means “queen” in Russian, and because the piece has more mobility with this tiling (6-8 squares instead of the four a ferz has on a square board)

- I have, in the last 28 years of speculating about this variant, considered pieces with circular moves. One issue with circular moves is that chess doesn’t have circular moves, so they might not be very intuitive for chess players, and because they can make the C3, C6, F3, and F6 cells too powerful.

- It’s possible to play Go with this board: One Go variant would be played inside the cells, where each piece would have three or four liberties (unless on the edge or next to another piece), depending on whether the cell was a square or triangle. It would also be possible to play Go on the corners of the cells; here each piece would normally have five liberties. In both cases, a larger board would be closer to 19x19 Go.

- There are 360 possible starting positions if we shuffle the pieces along the back row; it might make more sense to have the knights on the outside, the guards in the middle, and the rooks next to the king.

- Playing with Shogi style drops is also a rule I considered while inventing this variant. This is an optional rule, but not an official rule (so it can be played with normal chess pieces; just place a checker or coin under promoted pawns).

- Other possible optional pieces include: a piece which moves forwards or backwards like a rook, but otherwise like a guard, akin to Chu Shogi’s Sugyo (vertical mover); a piece which combines a rook and knight (a cardinal or marshal, if you will; I would place them on D1 and D8); and a piece which combines the guard and knight (a centaur). The Zillions file includes a variant with the cardinal on the board (pawns still promote to rooks in the variant). Some other piece ideas: Double move guard: Moves like a guard, but twice in one turn. Slightly more powerful than a knight. Semi-Cardinal: Moves like a rook when on a triangle tile. Moves like a knight when on a sqaure tile. Hybrid knight/guard: Moves like a guard on square tiles; moves like a knight on triangle tiles. Sideways pawns: Allow pawns to move one square sideways without capturing. Probably makes it a completely new game, just as Kramnik’s sideways pawns variant (normal chess, but pawns move sideways without capture) for a very different game (sideways pawns is another variant in the Zillions file)

- A combination of the modified Ko rule and the end zone win rule greatly reduces (if not eliminates) draws. Because of the geometry of the board, one king can not block the other king from reaching the end zone (there is no opposition in Turtle Shell Chess).

- The “stop an attack if it causes repetition” rule is a simplification of similar rules in Xiangqi (Chinese chess). For an example of this in a real world game, let’s look at Fischer-Tal Leipzig 1960. Here, after 21... Qg4+ by Tal, the game was drawn because of 22. Kh1 Qf3+ 23. Kg1 Qg4+ 24. Kh1 Qf3+ and so on. Using Turtle Shell rules, since the loop begins at 22. Kh1 and repeats with 24. Kh1, we look at the number of possible capturing moves at each stage in the loop, where each ply in the loop is looked at precisely once: 22. 1 attack (Qh7xe7) 2 attacks (Qh7xe7; Qf3xh1) 23. 1 attack (Qh7xe7) 2 attacks (Qh7xe7; Qg4xg1) and the loop repeats on move 24 so we look no further. For both moves (4 plies) in the loop, the board has more threats when Black has moved (4 total across the loop: 2 attacks both times Black has moved) than when White has moved (2 total across the loop: 1 attack each time White has moved), so Black is the one who needs to break the loop if this 1960 Chess game had Turtle Shell repetition rules.

- This variant has the name Turtle Shell Chess with each word in its name capitalized.

See also

- Parachess by Tony Paletta

- George R. Dekle Sr. has made a number of chess variants on different tilings: Triangular chess, Tri-chess, Trishogi, Masonic chess, Masonic shogi, Cross chess, Hexshogi, etc.

- Crazy 38’s uses an unusual board, albeit one with (mostly) square tiles.

- There are enough hexagonal chess variants out there that there is an entire category for them.

- Onyx is a connection game which uses a similar (if not the same) tiling.

Copyright

I dedicate the rules of this game and all graphics and code illustrating this game to the public domain.

This 'user submitted' page is a collaboration between the posting user and the Chess Variant Pages. Registered contributors to the Chess Variant Pages have the ability to post their own works, subject to review and editing by the Chess Variant Pages Editorial Staff.

This 'user submitted' page is a collaboration between the posting user and the Chess Variant Pages. Registered contributors to the Chess Variant Pages have the ability to post their own works, subject to review and editing by the Chess Variant Pages Editorial Staff.

By Samuel Trenholme.

Last revised by Samuel Trenholme.

Web page created: 2022-05-10. Web page last updated: 2022-05-10